The Renaissance of the Great Suez Canal

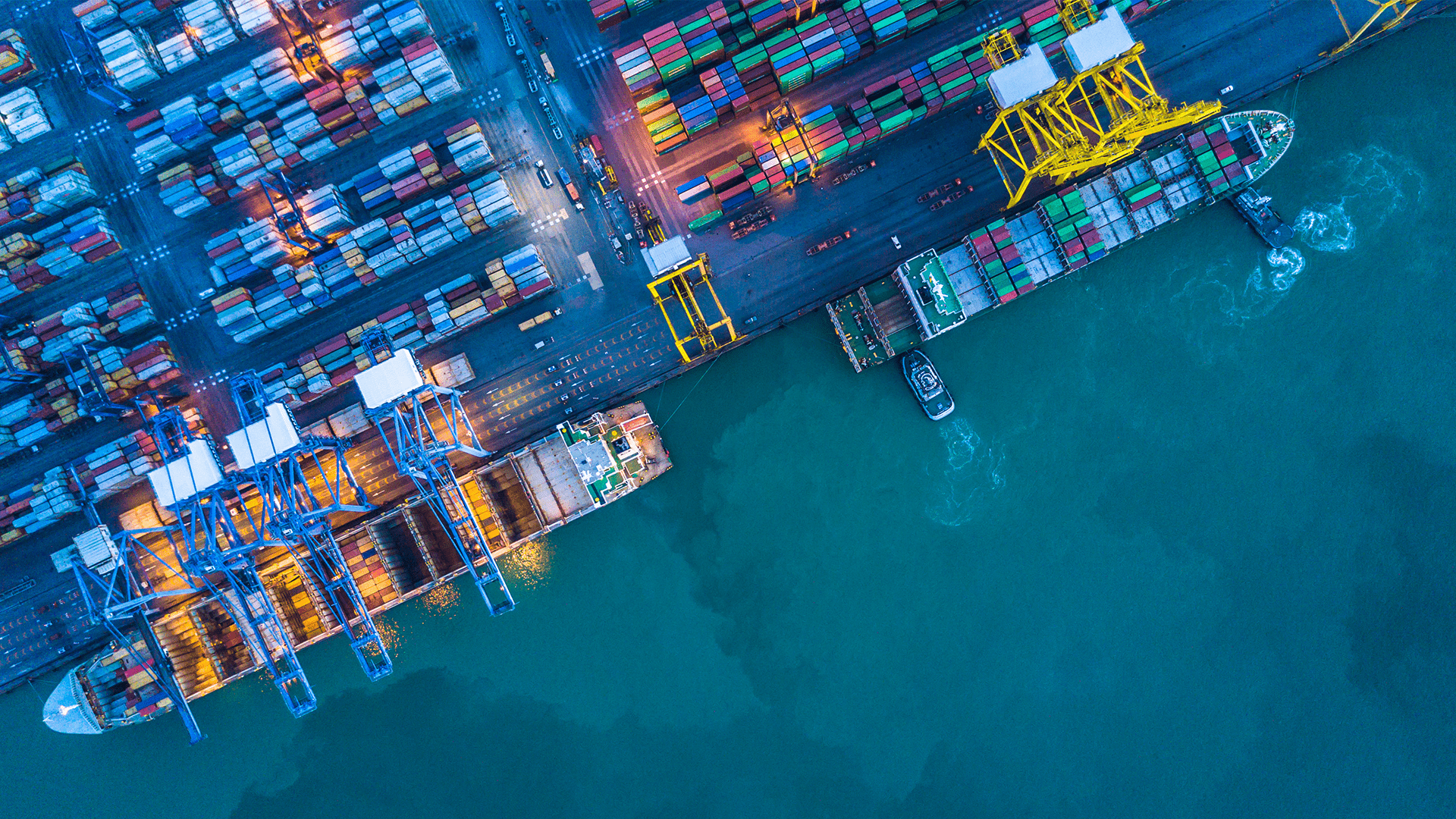

The tectonic plates of world trade are shifting. Southeast Asia replacing China as the world’s manufacturing powerhouse has vast implications for international shipping routes, ports, and supply chains, particularly in the United States. The gradual shift in shipping trade routes is further complicated by new environmental policies, increased climate risks, and the need to accommodate emerging generations of supercarriers. Ports on both US coasts are already responding, and as with any upheaval, there will be winners and losers.

During the last few decades, ports located on the West Coast of the US (USWC) have commanded a larger share of the country’s trade industry, than their counterparts on the Atlantic Coast. This trend was largely due to the dominance of China as Asia’s premier manufacturing hub. However, since 2006 there has been a gradual shift towards US East Coast Ports (USEC), helped by the expansion of the Panama Canal to accommodate vessels of 14,000 twenty-foot container equivalent units (TEU). During this period, traffic to USWC consolidated around the ports of Vancouver and Los Angeles/Long Beach, which together account for approximately 75% of all USWC container traffic.

In 2022, the freight handled by USEC ports exceeded the USWC by 46% to 45%. This trend is likely to continue due to the shorter and faster route from Southeast Asia, especially from India, which now has the US as its largest trading partner. This route uses the Suez Canal, which can accommodate the large 24,000 TEU supercarriers built to realise economies of scale and lower costs. Additionally, unlike the Panama Canal, the Suez Canal has not been affected by climate change so far.

Problems in Panama

By contrast, the Panama Canal is experiencing the worst drought conditions in 73 years. And the long-term prognosis is not rosy either. Scientists indicate that El Niño, the cyclical warming of ocean water in the equatorial Pacific, is being exacerbated by man-made climate change.

Earlier in 2023, the drop in the canal’s water level caused the Panama Canal Authority (PCA) to impose a 20% draft restriction on vessels and reduce the number of daily crossings. The resulting costly delays and lower volumes show no signs of changing with the PCA saying that it “aims to maintain a maximum draft of 44ft or 13.4m through the remainder of the current year and part of 2024.” Worse still, the number of daily crossings will also be reduced further until February 2024.

The number of daily crossings went from 36 to 32 in August 2023 and is expected to reduce as low as 18 by February 2024. As a result, shippers are now bidding feverishly for the two daily vacant crossing times the PCA puts to auction. On 8 November, Japan’s Eneos Group made a record queue-jumping bid of $3.97 million, which is more than $1 million higher than the previous top bid of $2.85 million made in October. In comparison, the usual crossing fee is around $900,000.

The impact of climate -related issues on the Panama Canal is likely to benefit the Suez Canal. However, insurers are concerned over regional tensions escalating and a possibility of a repeat of the disastrous Ever Green u-turn. Neither are champagne corks popping just yet for the USEC ports. The looming overcapacity in the container industry will drive shipping companies to deploy larger vessels on longer routes, such as through the Suez Canal, which can absorb more tonnage. Yet, unlike their larger USWC and European counterparts, no port on the USEC can accommodate the new 24,000 TEU supercarriers.

US ports play catch-up

The increasing size and capacity of container carriers is nothing new. Vessels that are too large to go through the Panama Canal – such as those at 14,000+ TEU – already make up 14% of the total fleet and a significant 26% of future orders.

Naturally, USEC ports are scrambling to dredge and invest in infrastructure to compete for a lucrative part of the Southeast Asia-Suez-Atlantic pie.

The Port of Savannah in Georgia is deepening its channel to increase its depth up to 52ft (15.85m). This will enable the Port to accommodate and handle vessels up to 22,000 TEU. The Port of Charleston did the same last year, and the Port of Norfolk Virginia is planning to dredge up to 55ft feet (16.76m) by 2024 to provide two-way traffic for the largest supercarriers.

Finally, it’s worth noting that USEC ports have experienced longer periods without serious labour disputes than their west coast rivals, although this may be put to the test when new contracts are up for negotiation.

This rebalancing of international trade routes to the US is nothing new and will no doubt happen again. Presently, the pendulum swings in favour of the USEC ports and Suez Canal.

For now, the unpredictability of the Gulf region and the threat of climate change are the most pressing concerns. The latter must not be lost on policymakers, for a world without a functional Panama Canal is almost unthinkable.

This article was originally published in The Maritime Executive on 1 December 2023.

![[object Object] [object Object]](https://www.royalhaskoningdhv.com/-/media/images/employees-profile-pics/h/helbing-jolke.jpg?h=500&iar=0&w=500&hash=FF6007EA034072AAA2CCE1272FC66A75)